Dieser Beitrag ist auch verfügbar auf:

Deutsch

For many people, 24-hour care is an important form of assistance without whom home care would often not be possible. This Friday, February 20, the Austrian Care Development Commission, composed of representatives from the federal government, states, municipalities, and cities, will meet to discuss this topic. The commission is responsible for the further development of the care system, which is beginning to struggle due to demographic change.

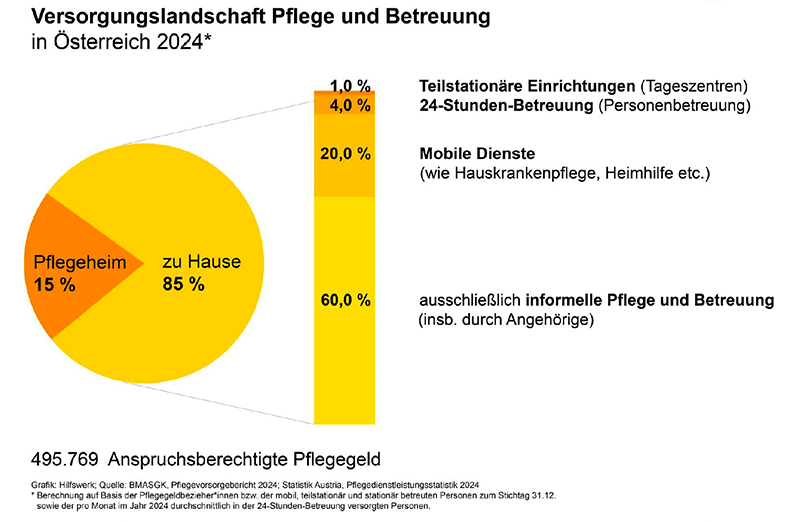

Rising demand as a result of demographic ageing is coming up against tight budgets and an increasing shortage of specialists and workers – putting the care system under noticeable pressure. At the same time, care is increasingly shifting to the home environment: around 85% of the people affected are cared for and supported at home by family members. This significantly increases their financial and organizational burdens. In many places, the outpatient support system is unable to keep pace with the dynamic demand and is developed very differently depending on the federal state.

This time, the organizations that organize and offer this assistance – such as Caritas, Hilfswerk and Malteser Care – are not represented at this commission’s table. They are calling for an increase in funding and a more realistic income threshold for this. This is because many people currently fall outside the subsidy and cannot afford official 24-hour care. The aid organizations fear that “unrealistic decisions” will lead to an exodus of workers to surrounding countries and a drift into unregulated illegal employment.

Cared for at home: Desired by many and economically more favorable

Being cared for at home is a frequently expressed wish of those affected – and is becoming increasingly difficult to finance. Especially when 24-hour care is required: The costs are around EUR 3,500 per month, with a subsidy of EUR 800. When it was introduced in 2007, the funding amount remained unchanged at EUR 550 per month until 2022. In 2023, it was first increased to EUR 640 and then to EUR 800. It has not been adjusted for high inflation since then.

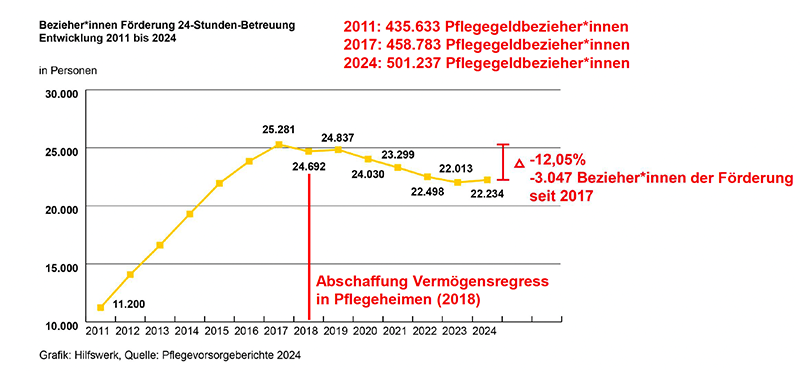

The problem: Although the subsidy was gradually increased, the income limit was not. This has remained unchanged at EUR 2,500 since 2007 – if the income is higher than this, families no longer receive a subsidy. Adjusted for inflation, this limit should actually be at least EUR 4,055 per month. For this reason, according to Elisabeth Anselm, Managing Director of Hilfswerk Österreich, more and more people are falling out of this support scheme.

As there is no alternative to care, those who cannot afford the additional private payments will have to go into a nursing home. These are already at their limit due to the shortage of skilled workers and labor, and we are at the beginning of demographic change. The costs for the public sector are quite different: The average annual net expenditure for a care place in a nursing home is EUR 38,728. In comparison, 24-hour care costs EUR 9,980 and mobile services EUR 6,307.

From an economic perspective, every patient who is cared for at home is therefore a gain. Nevertheless, there is an imbalance that is incomprehensible to the representatives of care organizations: the lion’s share of the money still goes to inpatient care, even though 85% of care is already provided at home. In other words, the money does not follow demand and therefore places an additional financial and organizational burden on inpatient care.

Drift into unregulated undeclared work

The system of 24-hour help has been established since 2007: The caregivers are self-employed and bill the family they support. Around 30,000 families currently make use of this service. The carers – mostly from Eastern and South Eastern Europe – come to the country for 2 to 3 weeks at a time, live with the families and look after those in need of care on a day-to-day basis. This relieves the families and allows them to go to work, for example.

If the system collapses due to reduced subsidies, which is also possible if it is not adjusted to the increased everyday costs due to inflation, other countries are already waiting for these forces: according to Anselm, Austria is currently losing carers to Switzerland, Germany and northern Italy. This can be seen in the trade licenses, which are falling despite the high demand.

There are also fears of a drift into the completely unregulated black market – i.e. unregistered or untrained workers. Around 850,000 foreign domestic helpers are active in Germany, as the social scientist Pof. Dr. Thomas Klie explained in his keynote speech at the German symposium on “Caring Communities”: “That’s more full-time jobs than in all outpatient care services combined. Without these tolerated structures below the level of legal attention, our care system would collapse.” On the one hand, there are the regulated professional care structures full of regulations and bureaucracy. On the other hand, an informal sector is emerging out of necessity that is difficult to keep track of.

In order to keep 24-hour care stable in terms of quality and support, the care organizations are therefore calling for a doubling of funding to EUR 1,600 and a valorization of the income limit to EUR 4,055. The Care Development Commission will decide on the future of 24-hour care in Austria on Friday – we will report back.

Author: Anja Herberth

Chefredakteurin